On June 28, 2018, the Senate overwhelmingly passed its version of the 2018 farm bill with an historic 86 to 11 vote (U.S. Senate, Roll Call Vote 143). Senate passage followed on the heels of a very narrow, party-line re-vote in the House on June 21st finally passing the bill 213 to 211 (U.S. House of Representatives, Clerk, Roll Call Vote 284). Having cleared these two key hurdles in the reauthorization process, the 2018 farm bill debate heads to a conference committee to resolve the differences between the House and Senate versions. This article reviews what are likely to be the top five issues for conference negotiations.

Issue #1: Changes to SNAP

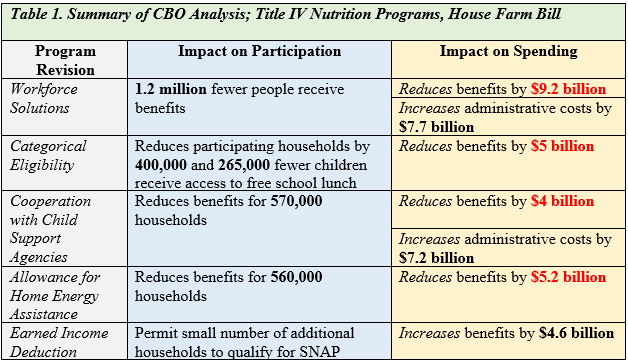

The single biggest challenge for conference negotiators will be the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). The problem is not just that the House and Senate took vastly different paths on policy, with very different results, but that the House is operating under partisan and ideological perspectives that differ from those in the Senate; such differences likely to add to the challenges for negotiations. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) analyses and cost estimates provide the clearest view. CBO estimates that the House bill would spend an additional $463 million on those programs (CBO Cost Estimate, May 2, 2018). While CBO estimates that the House bill would increase spending in Title IV, controversy flows from some of the primary ways in which the House proposes to change SNAP. Most notably, the House bill reduces the number of people receiving benefits and reduces benefits received per household, while increasing the administrative costs of the program. Table 1 summarizes CBO’s analysis and cost estimates, specifically the increases or decreases in spending and the impacts on participating people and families (see also, farmdoc daily, May 24, 2018, and April 26, 2018).

By comparison, CBO estimates that the Senate bill would spend a total of $6 million less on Title IV Nutrition programs (including SNAP) over 10 years (CBO Cost Estimate, June 21, 2018). The Senate bill makes minor revisions to SNAP, including to the existing work requirements at an added cost of $235 million for new grants to states (FY2019-2028) and for the certification period ($205 million increase). The Senate also proposes administrative funding increases for improving the electronic benefit transfer (EBT) system for SNAP participants, as well as other changes to increase spending for food insecurity assistance (total increase, $562 million). The Senate bill mostly offsets the increases by requiring states to use a national database to prevent duplicative benefits ($588 million reduction) and lowering or eliminating bonuses to states for performance and error rates ($420 million reduction).

The few amendments considered on the Senate floor added emphasis to the differences between the House and Senate on SNAP. By a vote of 68 to 30, Senators resoundingly rejected an amendment that would have added the House workforce solutions (U.S. Senate, Roll Call Vote 141). This vote would appear to signal that the House’s additional work requirements for SNAP could complicate the conference committee’s work.

Issue #2: Payment Limits and Reforms

The House and Senate are also far apart in terms of the eligibility requirements for farm programs and how much any farmer can receive from the commodities programs. The House farm bill proposes changes in eligibility requirements that would permit families and newly-defined pass through entities to increase payments. The House also proposes exempting pass through entities from adjusted gross income (AGI) requirements while removing application of payment limits to marketing assistance loan gains and loan deficiency payments (farmdoc daily, June 19, 2018).

By comparison, the Senate proposes to tighten eligibility requirements with a specific focus on reducing the number of individuals who can claim to be eligible for farm program payments under the actively engaged in farming requirement. The Senate proposal focuses on what is known as the management loophole, which permits some individuals to qualify for payments based on only contributing management to the farm operation. The bill defines and increases the requirements for claiming a significant contribution of active personal management to the farming operation. It also restricts farm operations from qualifying more than one individual as actively engaged in farming based on management contributions. Combined, these provisions would limit a farm from collecting additional farm program payments by adding managers to the operation, an issue that the Government Accountability Office has repeatedly highlighted as a method of abusing the programs (GAO June 5, 2018). It also builds on the efforts to tighten this requirement during the 2014 farm bill debate (farmdoc daily, April 8, 2015).

Issue #3: Reductions to Conservation

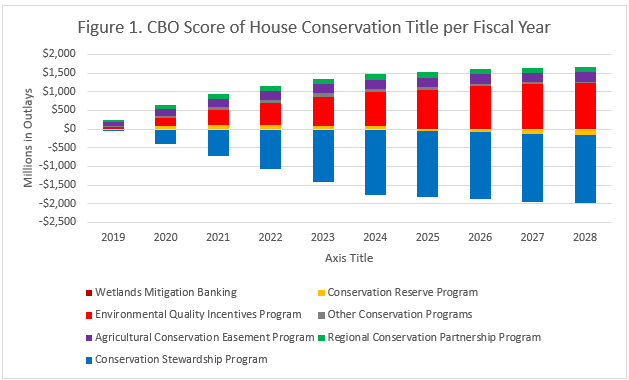

The House position again represents the more drastic change to existing policy. The House farm bill proposed to eliminate the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) and increase funding for the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP), while adding authority for stewardship contracting in EQIP. In total, these changes would result in a net loss of nearly $5 billion over 10 years for working lands conservation (see, farmdoc daily, June 7, 2018). The House also proposes to increase the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) acreage cap by 1 million acres per fiscal year, ending at 29 million acres in FY 2023. The House proposes to cover the costs of additional acres by reducing per-acre rental payments to 80 percent of the average county rental rate as well as reducing rental rates further for acres re-enrolled in the program. Finally, the House proposed increasing funds for the Agricultural Conservation Easement Program (ACEP) and the Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP) by $3.5 billion over the ten-year period (FY 2019-2028). In total, CBO estimates that the House farm bill would reduce conservation funding by $795 million over 10 years. Figure 1 illustrates the CBO score (increase or decrease in direct spending) for the conservation title in the House farm bill from FY 2019 to 2028.

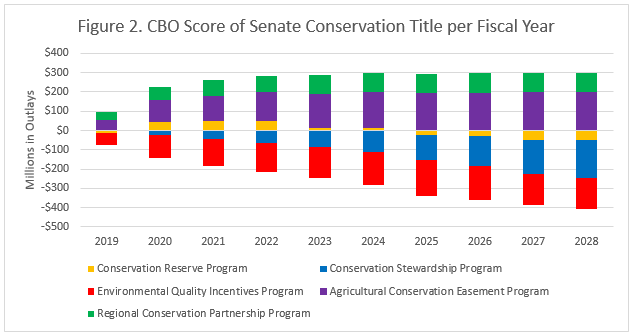

By comparison, the Senate farm bill would neither increase nor decrease total conservation spending over the ten-year budget window. The Senate bill increases the CRP acreage cap to 25 million acres, paying for the costs by reducing rental rates to 88.5 percent of the county average rental rate. It also creates a new Conservation Reserve Easement program to permit acres about to leave CRP to enroll under a permanent easement to keep the acres out of farming. This program would cost $1.8 billion (FY 2019 to 2028) according to CBO. The Senate increases funding for ACEP and RCPP by $2.5 billion. The increased spending is offset from within the conservation title by reductions to CSP and EQIP. The Senate farm bill proposes to reduce enrollment of new acres in CSP to 8.797 million acres per fiscal year (down from 10 million per fiscal year in the 2014 Farm Bill), saving $1 billion over 10 years. It would reduce EQIP by $1.5 billion (FY 2019-2028). Figure 2 illustrates the CBO score (increase or decrease in direct spending) for the conservation title in the Senate farm bill from FY 2019 to 2028.

For conference negotiators, making large reductions to conservation programs and spending may be particularly ill-timed given that farmers are currently experiencing multiple years of relatively low crop prices, declining incomes and erosion of their farm financial health (see, farmdoc daily, June 26, 2018). Recent events with regard to trade may add further concerns to reducing conservation spending (see, farmdoc daily, April 17, 2018 and June 8, 2018). Farmers, however, remain under intense pressure to improve the impacts on natural resources such as soil and water from modern production; from nutrient loss reduction to improve water quality to sustainable sourcing to meet consumer demands. The practices necessary to meet these pressures and invest in efforts for the long-term health of soils and the environment come with significant costs to the farmer; benefits are difficult to measure and can take years to achieve (see, farmdoc daily, June 28, 2018). Arguably, this might be the worst possible time to cut spending on conservation, particularly on working lands conservation assistance that keeps land in farming but helps offset the costs of implementing conservation practices and systems.

Issue #4: Differences on Farm Policy; ARC vs. PLC; Cotton & Dairy

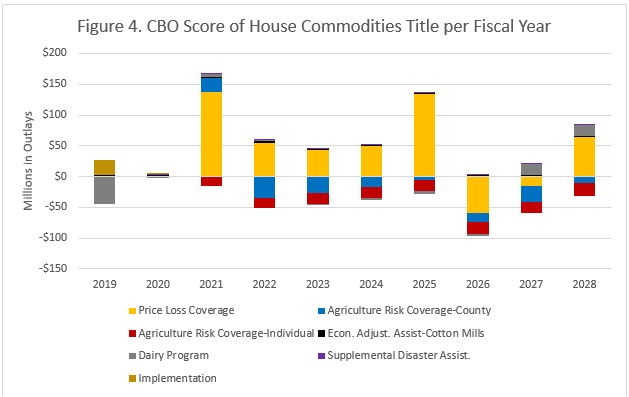

Compared to the proposals for SNAP, conservation and payment eligibility and limitations, the House and Senate are not that far apart on farm programs. Most of the changes represent differences in regional perspectives for farm policy; revenue programs preferred by Midwestern interests and price programs preferred by Southern interests. CBO estimates that the House farm bill would increase commodity program spending by $200 million over the ten-year window (FY 2019-2028), while the Senate farm bill would reduce spending by $400 million.

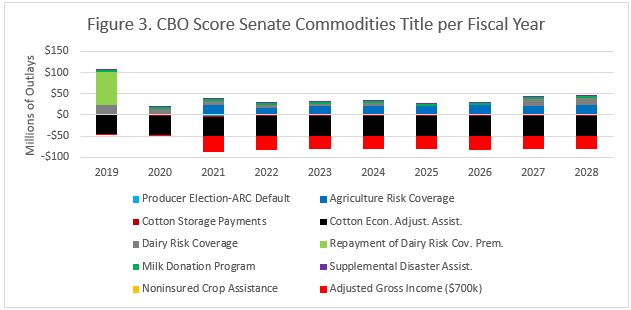

The Senate farm bill favors the Agriculture Risk Coverage (ARC) program by making it the default choice in the election and improving the benchmark yields through the use of a trend-adjusted yield factor. The Senate farm bill would also permit farmers to revise their program election in the 2020 crop year. It does not revise the Price Loss Coverage (PLC) program but does eliminate special payments for cotton storage and for economic adjustment assistance to users of upland cotton. The Senate farm bill also revises the dairy program, renaming it Dairy Risk Coverage. Figure 3 illustrates the CBO score for the Senate farm bill commodities title from FY 2019 to 2028.

The House farm bill favors PLC over ARC, adding $408 million over ten years to PLC and cutting $253 million from ARC, including elimination of the ARC-individual coverage option in the program. The House also added a provision to PLC that would permit reference prices to increase up to 115 percent of the statutory reference price based on a five-year Olympic moving average price (see, farmdoc daily, May 17, 2018). Other minor revisions in the House bill include some reductions to the dairy program and an increase in funding for the economic adjustment assistance to cotton textile mills. Figure 4 illustrates the CBO score for the House farm bill commodities title from FY 2019 to 2028.

Issue #5: Politics and the Legislative Calendar

The final issue for conference and completion of a farm bill in 2018 is less an issue concerning specific policies and programs. It is, instead, an issue of the combined challenges from the current political environment, the pending midterm elections, and the shortened legislative calendar. The House was unable to resolve the immigration issue that contributed to the farm bill’s initial defeat on the floor. With the retirement of Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy, the Senate will quickly become consumed by a presumably contentious consideration of his replacement. Congress also needs to address the lack of appropriations bills, likely passing a continuing resolution.

If past practice holds, Congress will recess for most of the month of August and return in September. It is likely to recess again for campaigning in late September or early October. This does not provide much time for conference negotiations nor passage of a negotiated conference product. Partisan political fights over SNAP in particular could not only complicate conference negotiations but stand as a significant barrier to passage in either the House or the Senate, depending on which path the conference committee takes. In short, acceptance of the House position on SNAP would appear unlikely to pass the Senate; acceptance of the Senate position on SNAP would appear possible with substantial support from Democrats to pass the House but would likely be opposed by Republicans and possibly the Administration.

Concluding Thoughts

For those who support passage of the farm bill, the news heading into Independence Day provides reason to be cautiously optimistic that re-authorization will be completed in a timely manner but there remain reasons for concern. The 86 votes in favor of a farm bill in the Senate represents an historic achievement; it was the highest vote total for a Senate farm bill in the bill’s 85-year history. Aside from specific programs, this historic result offers a strong argument in favor of a bipartisan farm bill that avoids the controversy and opposition to reducing SNAP assistance for low-income persons and families. Among the many differences to be resolved, the proposed changes to SNAP in the House farm bill appear to be the most difficult. Conference negotiations are also likely to focus on farm program payment limits and eligibility requirements, as well as spending priorities for conservation policy; resolving conservation may be particularly influenced by the current state of the farm economy and pressing demands on farmers in terms of nutrient loss reduction, soil health, and sustainable sourcing. Conference negotiators likely have a very short window to reach agreement and get a bill through a Congress increasingly consumed by the midterm elections. This political reality should counsel against sweeping, controversial and narrow, ideological fights. To put a finer point on it, if supporters want a farm bill completed on time, the Senate version has to look particularly attractive at this fraught political moment.

References:

Burak, S., K. Baylis and J. Coppess. “Gambling on Exports: A Review of the Facts on U.S. Agricultural Trade.” farmdoc daily (8):105, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, June 8, 2018, https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2018/06/gambling-on-exports-review-facts-us-agri-trade.html

Congressional Budget Office, Cost Estimate, H.R. 2, Agriculture and Nutrition Act of 2018 (May 2, 2018), https://www.cbo.gov/publication/53819

Congressional Budget Office, Cost Estimate, S. 3042, Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 (June 21, 2018), https://www.cbo.gov/publication/54092

Coppess, J. “Reviewing the USDA Proposal to Limit Farm Program Payment Eligibility.” farmdoc daily (5):64, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, April 8, 2015, https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2015/04/reviewing-usda-proposal-to-limit-payment-eligibility.html

Coppess, J. and B. Gramig. “Reviewing Directions in Conservation Policy: CSP and EQIP in the House Farm Bill.” farmdoc daily (8):104, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, June 7, 2018, https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2018/06/reviewing-directions-in-conservation-policy-html.html

Coppess, J. and T. Kuethe. “Mapping the Fate of the Farm, 2018 House Edition.” farmdoc daily (8):95, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, May 24, 2018, https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2018/05/mapping-the-fate-of-the-farm-2018-house-edition.html

Coppess, J., G. Schnitkey, N. Paulson and C. Zulauf. “Progress and Potential Hurdles for the 2018 Farm Bill.” farmdoc daily (8):112, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, June 19, 2018, https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2018/06/progress-and-potential-hurdles-2018-farm-bill.html

Coppess, J., G. Schnitkey, N. Paulson “Comparing Price Policy Directions in the 2018 Farm Bill Debate.” farmdoc daily (8):90, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, May 17, 2018, https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2018/05/comparing-price-policy-directions-in-the-2018-farm-bill-debate.html

Coppess, J., G. Schnitkey, N. Paulson and C. Zulauf. “Initial Review of the House 2018 Farm Bill.” farmdoc daily (8):75, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, April 26, 2018, https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2018/04/initial-review-of-the-house-2018-farm-bill.html

Swanson, K., G. Schnitkey, J. Coppess and S. Armstrong. “Understanding Budget Implications of Cover Crops.” farmdoc daily (8):119, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, June 28, 2018, https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2018/06/understanding-budget-implications-of-cover-crops.html

Swanson, K., G. Schnitkey, J. Coppess and N. Paulson. “Five-Year Income Projections for Grain Farms.” farmdoc daily (8):117, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, June 26, 2018, https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2018/06/five-year-income-projections-for-grain-farms.html

Swanson, K., G. Schnitkey, T. Hubbs, J. Coppess, N. Paulson and C. Zulauf. “Impacts of Chinese Soybean Tariffs on Financial Position of Central Illinois Grain Farms.” farmdoc daily (8):68, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, April 17, 2018, https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2018/04/impacts-of-chinese-soybean-tariffs.html

U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Farm Programs: Information on Payments [Reissue with Revisions Jun. 05, 2018],” GAO-18-384R (May 18, 2018), https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-18-384R