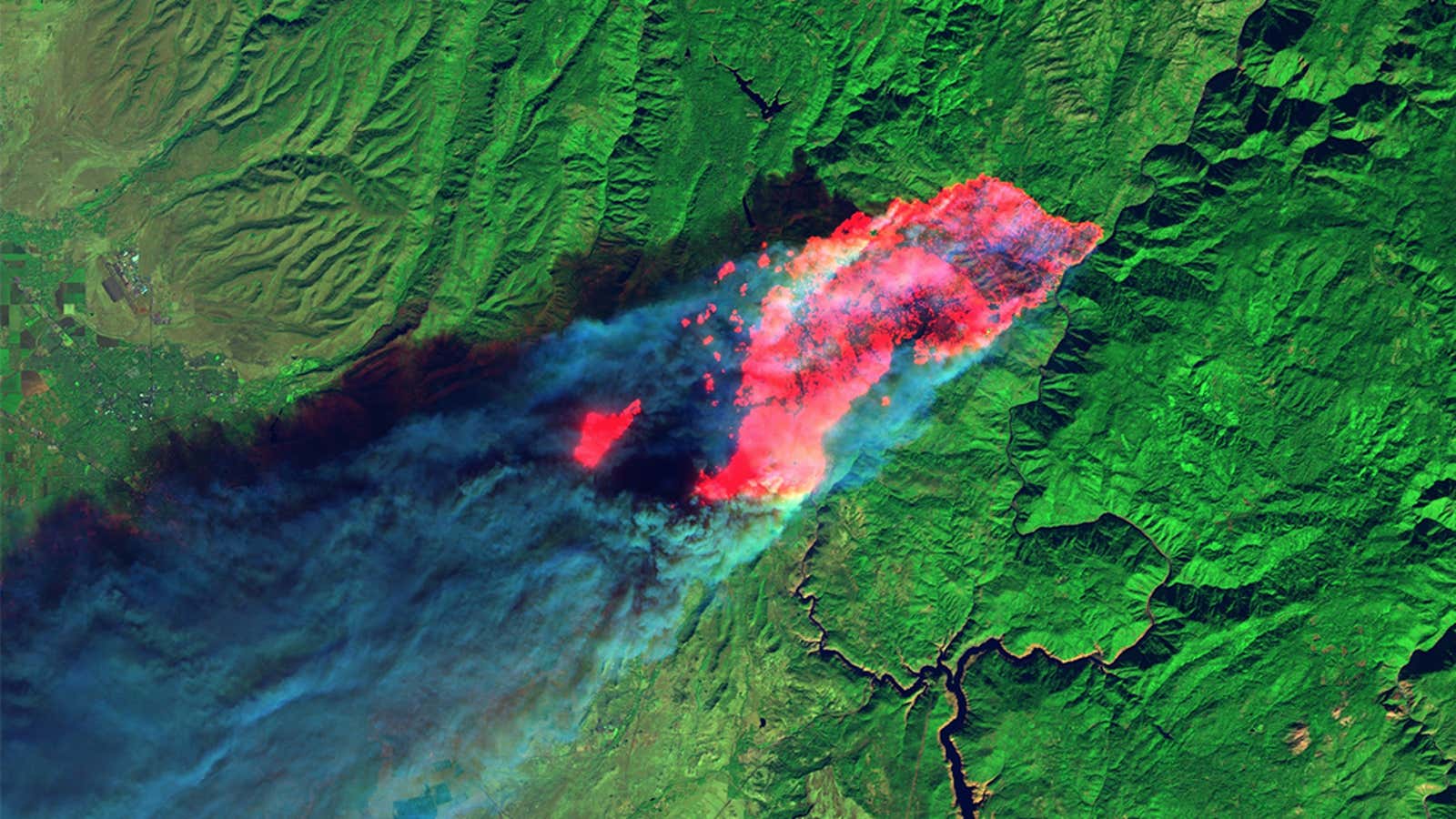

California is burning. An area the size of Delaware has gone up in flames in 2018, as more than 7,000 fires have ripped across the state, according to the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. The latest conflagrations are the Woolsey and Hill fires near Los Angeles, and the Camp Fire north of San Francisco. The latter is now the state’s deadliest with 63 dead and 631 missing. It was only 40% contained as of Nov. 15.

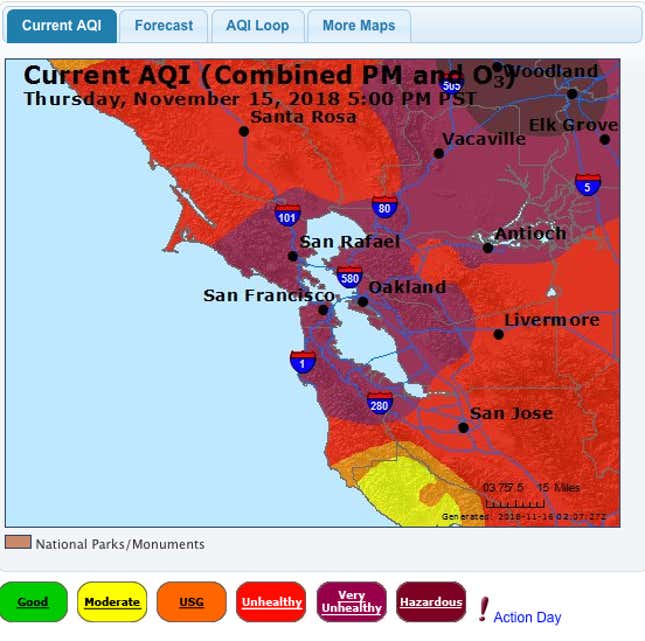

That fire is causing the worst air pollution in history for the Bay Area and northern California, says John Balmes, a physician at the University of California, Berkeley, who sits on the California Air Resources Board. Looking at air pollution around the world, you can’t get much worse than San Francisco at the moment. Only Dhaka, Bangladesh, was more polluted on Friday (Nov. 16) among major cities (Sacramento and San Francisco held top spots the previous day).

We’re witnessing a phenomenon that isn’t going away. Extremely dry conditions linked to climate change are fanning wildfires across the state. Scientists expect this to get worse as rains fail, and temperatures rise. “The concern is that this is the new normal,” says Balmes. “If we have one of these after another, that’s going to move us toward living in Delhi [one of the world’s most polluted cities].”

To better understand what’s happening, and what comes next, Quartz interviewed doctors, public health officials, and atmospheric scientists.

What exactly is in the smoke?

A good analogy is to think of the particles in the air as very tiny droplets of candle wax, says Ronald Cohen, an atmospheric chemist at the University of California, Berkeley. Raging wildfires send towering plumes of these particles into the atmosphere that spread over the landscape. These floating carbon molecules were once trees, vegetation, and towns.

The smallest particles measure less than 2.5 microns across (30 times smaller than a human hair). Because they can pass through the lungs into the bloodstream and cause health problems, they are the most dangerous. Volatile organic compounds and nitrogen dioxide are also present, although less is known about their health effects.

How bad is this air pollution?

Very bad, although healthy people may not experience immediate problems. Government data from real-time air monitoring stations show San Francisco’s air quality index (AQI) score hit 221 on Nov. 16. That’s well into the “unhealthy” range. Smaller towns closer to the fire exceed 470. That’s still better than the worst days in India or China, where cities can exceed 900 for days, but it’s unprecedented for the Bay Area. The air quality index in the US rarely exceeds 300. IQAir, which has air monitoring stations around the world, ranked San Francisco second for global urban air pollution on Nov. 16.

To put this in perspective, northern California’s air quality has been fluctuating between 200 to 470 micrograms of particulate matter (PM) per cubic meter (those 2.5 micron particles considered most dangerous). Berkeley estimates that’s equivalent to smoking about 10 cigarettes per day (its rule of thumb is one cigarette is equal to each additional 22 micrograms of PM2.5 per cubic meter). For comparison, the world’s most polluted cities may see particulates soar to 1000 micrograms on their worst days, the equivalent of several packs of cigarettes per day.

What are the health effects?

In northern California, the smoky air can lead to infections and asthma. For the most vulnerable, such as the elderly and those with respiratory problems, it can trigger (paywall) heart attacks, stroke and complications requiring an emergency room visit. Healthy individuals have less to worry about. Short-term effects are mild—eye and lung irritation and difficulty breathing—but we aren’t entirely sure about the long-term effects, says Balmes.

Scientists do know that chronic exposure to severe air pollution damages the human body. Low-birth rates, asthma, cardiovascular disease, immune suppression, and sclerotic arteries causing heart attacks and strokes have all been linked to air pollution. The World Health Organization calls air pollution the world’s largest environmental health risk. The British medical journal Lancet blames poor air quality for 9 million premature deaths worldwide in 2015.

Scientists are testing two hypotheses about how such tiny particulates damage the body. One ideas is that the particulates are absorbed into the body and act as irritants in our lungs and soft tissues, causing inflammation. The second is that particulates cause oxidative stress by generating charged particles known as free radicals in the body, leading to cardiovascular disease.

When will the smoke go away?

It takes a week or more for particulates to settle out of the atmosphere, and onto the ground. With fires spewing trillions of more particulates per second into the air, the smoke will not abate until the fires are controlled, or the winds shift. Neither seems likely in the coming days, forecasters predict. Although October 1 marked the official start to the wet season, no rain has fallen, leaving the state as arid as mid-summer. “It’s unprecedented,” meteorologist Craig Shoemaker of the National Weather Service told National Geographic. “It’s like a matchbox.”

Where’s the safest place to be?

Indoors is better than outdoors. Homes with air recirculating through quality filters (known as HEPA filters) are even better. Older buildings tend not to have tight seals or recirculating air that would cut down on the number of particulates. That’s one reason schools in Oakland and San Francisco decided to close on Nov. 16.

But if people can afford them (many cost hundreds of dollars), high-quality HEPA filters can remove the smallest particles, improving air quality in a room by as much as 75%. Staying indoors and limiting exertion outdoors are the best bet while the air pollution persists.

What if I have to be outdoors?

If you can’t avoid being outdoors, masks that say N95 or P100 can filter out 95% of the worst particulate matter, according to the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services and the California Department of Public Health. If you’re wearing surgical masks or bandannas, that’s totally ineffective at filtering out small particles. Masks also need to be tightly fitted to be effective. Although children are among the most vulnerable, masks are not designed for their faces, rendering them ineffective. If it’s not uncomfortably tight, it’s probably not working.

Will this happen in California again?

Yes. It’s a global phenomenon, but California is the test case. Fires far bigger than the Camp Fire rage around the world every year. People usually never experience them so intensely because they are far from populated areas, although fires in Alaska and Canada will darken the skies as far away as Colorado.

That’s changing, particularly in the western US. This year set new records for Bay Area air pollution, although the previous record was set only just last year.

In California, vast swaths of forestland, much of it dry and unburned for years, will likely go up in flames in the coming decades, writes Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles. California’s wildfire season, once June to late September, is now year round.

People are moving homes deeper into forests where wildfires leave them vulnerable: towns like 27,000-person Paradise, which burned to the ground in the Camp Fire. The US also still spends more on fire suppression than controlled burns that reduce the fuel for future infernos. Climate change will only make these mistakes worse.

“That’s really not sustainable,” says Balmes. “We’re going to have more situations like Paradise. Hopefully, a good outcome from this tragedy will be that we get serious about this.”