17 Things We Learned About Income Inequality in 2014

The Atlantic's Business editors break down the year's most divisive economic conversation.

Earnings growth for the richest Americans has been outpacing the income growth of the lower and middle classes since the 1970s, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities's analysis of data from the Congressional Budget Office. That means that income inequality is not a new concept. So why does it suddenly feel like such a big deal?

Well, in the wake of the recession, the pinch of sluggish wages and the lackluster job market are more acute for more Americans. President Obama also played a part in the narrative, highlighting the issue during his 2014 State of the Union address, saying, “Inequality has deepened. Upward mobility has stalled. The cold, hard fact is that even in the midst of recovery, too many Americans are working more than ever just to get by—let alone get ahead.”

1) Where Things Stand Right Now

Income inequality isn’t just about the inability of some to afford the finer things in life. Research suggests that a wide gulf between incomes can have more pernicious effects, such as increased feelings of disenfranchisement, fewer opportunities for advancement, and increased poverty. Some economists have even suggested that a large gap between class incomes can lead to stunted economic growth. Between 2009 and 2012 the top one percent of Americans enjoyed 95 percent of all income gains, according to research from U.C. Berkeley. The same study found that income inequality may be at its most pronounced levels since 1928, the height of the stock-market bubble.

2) As Long As We're Still Growing, Right?

In theory, income inequality in a capitalist society is highly probable and maybe even a little bit desirable. After all, people need financial incentives to work hard and innovate. But inequality could also impair growth if those in the middle and at the bottom have no money to spend.

While it’s hard to argue definitively whether income inequality is good or bad for economic growth, research by the International Monetary Fund argues that high inequality is correlated with low economic growth—so redistribution might reduce inequality and boost growth. The OECD’s report on income inequality is more explicit, stating that income inequality has a negative and statistically significant impact on growth because of its impact on low-income households and their education outcomes. An S&P research brief also states that "increasing income inequality is dampening U.S. economic growth."

Basically, some income inequality is necessary and fine. The levels we’re seeing now? Not so good for the economy.

3) Piketty, Piketty, Piketty

Given that Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century dipped into data that spans centuries, it seems like he could’ve picked any year in the past decade to release his findings. He chose 2014, and unexpectedly—to the press and even to his publisher—the book took off. No fewer than three Nobel Prize winners have done work similar to Piketty’s, and yet for some reason he was the one to become identified with the topic of wealth inequality. Even though Capital was so deeply researched that it’d be foolish to call its success entirely a fluke, it’s undeniable that Piketty gave 2014’s book-buying public what it wanted: a well-dressed, well-educated European alternative to an Occupy movement that is still aimless and now rundown. No wonder it sold 80,000 copies in two months.

4) But What if Piketty Is Wrong?

And like any celebrity in 2014, Piketty was not immune to intense scrutiny. Chris Giles, the economics editor of the Financial Times, raised the first significant public concerns about Piketty’s data sets in late May, the month after the book was published. Piketty refused to acknowledge any problems with his numbers, insisting that his manipulations were deliberate and that his conclusions still stood. Reasonable people disagreed from all angles. Yes, the debate spoke to the murkiness of any economic data that’s more than a few decades old, but it also revealed a larger truth behind the bickering: The year 2014 was so focused on wealth inequality that a conversation about 18th-century financial data took on the emotional charge that Americans usually reserve for much more frivolous topics.

5) Goodbye, Middle Class

The growing gulf in earnings between America’s richest and everyone else means that the group that's historically fallen in the middle, living a life of neither luxury nor poverty, is shrinking. In 2013, median household income was $51,939, still eight percent lower than in 2007, the year before the recession started, according to Census data.

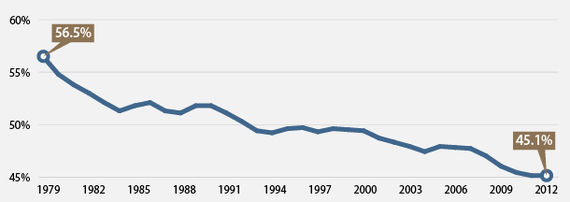

A recent report by the Center for American Progress shows that in 1979, a majority of American households (59.5 percent) had earnings that qualified them as middle class (defined as working-age households with incomes between 0.5 and 1.5 times the median national income). In 2012, the share of middle class families had fallen to 45.1 percent, indicating that American households have become more concentrated at the top and bottom of the earnings ladder.

Why is that a problem? For one thing, mobility: More of the middle class is migrating to the lower class due to stagnant incomes and the increasing cost of living—which means more Americans are struggling to make ends meet. That’s not just bad for families; it's bad for the economy. A recent study of income inequality at Washington University in St. Louis suggested that a depleted middle class can lead to a downturn in demand for goods and services, a bad outcome for businesses and the economy as a whole.

6) Will Millennials Make It?

Things look pretty rough for Millennials: Wages for young workers are falling, their preferences and economic circumstances make it incredibly hard for them to buy a home, and the best cities for them to get ahead in are the most expensive ones. And like most of America, they're not making enough money to save.

But how will Millennials climb out of this? That's the answer nobody seems to have. Will they leave the cities that are costing them so much? Or work in the health-care field, the exception to the falling wages rule? Or will they indeed be the first generation in decades to be worse off than their parents? The White House Council of Economic Advisers released a report this year on Millennials, and wrote this in the conclusion: "While there are substantial challenges to meet, no generation has been better equipped to overcome them than Millennials." Let's hope they're right.

7) Minority vs. Majority

In 2013, median income for a white household was $58,270, according to Census data. For Hispanics it was $40,963 and for blacks it was only $34,598. One minority group bucks the trend: Asians. In 2013, median earnings for Asian households was $67,035, surpassing the median income of all households.

The differences between household income nod to greater discrepancies between racial groups within the country. One major reason for the depressed incomes of blacks and Hispanics is the higher rate of unemployment for these groups. During the third quarter of 2014, white Americans age 16 and over had an unemployment rate of 5.3 percent, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. For Asians, unemployment was even lower, around 4.5 percent. But historically, blacks and Hispanics face higher rates of unemployment than their fellow Americans, and the recession and sluggish recovery has exacerbated high-unemployment rates for these groups. During the same period, Hispanic Americans had an unemployment rate of 7.3 percent and the unemployment rate for blacks was 11.7 percent, more than twice the rate of their white or Asian counterparts.

8) The Trouble's at the Bottom

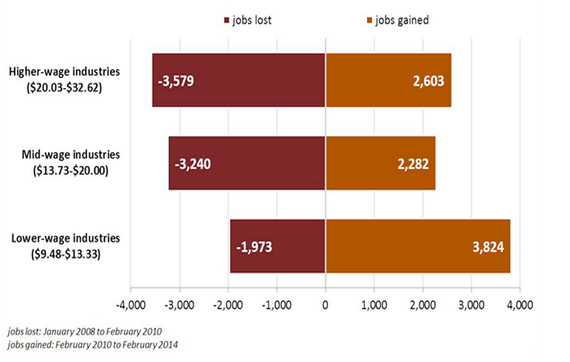

Yes, the economy is picking up steam and employers are finally creating jobs. But that doesn’t mean that the jobs created are the jobs needed to spur economic growth. Low-wage industries have added 3.8 million jobs since February 2010, although the industry lost just two million jobs during the recession, according to a report from the National Employment Law Project. In the meantime, higher-wage industries have added just 2.6 million positions during the recovery, although they shed 3.6 million jobs during the recession. Jobs in food service, retail stores, and temp firms are leading the recovery, according to the report—they accounted for 39 percent of private-sector employment gains in the past four years.

That’s problematic for many reasons, including the fact that many of those jobs pay minimum wage, which means less money in Americans’ pockets and potentially slower consumer spending—which accounts for about 70 percent of the U.S. economy. What’s worse, many service workers are finding that they aren’t able to get as many hours as they’d like, and that their schedules are unpredictable. That means minimum wage workers are struggling, even in states that have raised the minimum wage from the federal standard of $7.25. Many end up living in poverty, even though they have jobs. Not exactly the recovery America needed.

9) Sticky Floors and Glass Ceilings

Millennial women have closed the gender wage gap from previous generations. But a gap persists, and there is reason to think it could actually grow. According to the “sticky floor” theory of the gender wage disparity, women earn closer to their male colleagues in low-paying jobs and entry-level positions. But as generations age and move along in their careers, men take a lead over their female peers. It’s just one more reason why the entire economy might be better off if companies not only offered more maternity leave but also paternity leave, which would put new parents on equal footing. When a generation’s smartest women leave the workforce because they don't feel valued at the office, the entire country suffers from their withdrawal.

10) Maybe It's Time to Start Worrying About Men

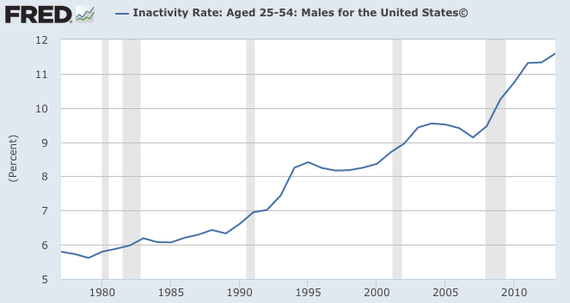

Women are catching up with men in the wage race not only because their wages are rising, but also because male employment is falling. The inactivity rate among prime-age men—that is, the share of men between 25 and 54 who are neither working nor looking for work—has been rising steadily since the early 1980s.

The trend shows no sign of abating. Of particular concern is the fact that the inactivity rate has grown more in the recovery than it did throughout the Great Recession.

Perhaps the most important explanations are that globalization and technology are making many routine-based jobs both cheaper and scarcer, and the housing bust has devastated construction employment.

11) Single Ladies, and Single Men

Three economists looked at who's marrying whom in the last 50 years and how that's affecting income inequality. In short, educated men and women did not always marry each other. In 1960, only 25 percent of men who graduated college married women who also had degrees. That trend is increasing: In 2005, that number was up to 48 percent. It's hardly surprising that men and women of similar education backgrounds would seek each other out, but "assortative mating" means more income inequality than if couples were randomly put together regardless of income and education.

Furthermore, income inequality and assortative mating are contributing to a marriage gap where higher earners can afford marriage, and low-income workers can't. Sociologist Andrew Cherlin argues that America is seeing a second era of the marriage gap (the first was during the Gilded Age, when income inequality was high and rising). The association shows that periods of lower income inequality lead to higher marriage rates across all income groups. Along with big cultural shifts in marriage, researchers are seeing record numbers of unmarried adults. Further, research shows that times of economic recession results in lower marriage and birth rates—but fewer divorces.

12) Politicians Sound Off

In one response to the topic of income inequality, Texas Governor Rick Perry reasoned that some level of inequality was preordained saying, “Biblically, the poor are always going to be with us in some form or fashion,” in an interview with The Washington Post.

But for the most part, regardless of party, political leaders agreed that growing income inequality and a shrinking middle class is problematic. That’s largely where the similarities ended. When it comes to causes and solutions, politicians had lots of ideas this year. In a speech, Senator Marco Rubio suggested that an increase in marriages and low-skill jobs could help bridge the gap. Senator Rand Paul of Kentucky pondered whether or not the fault lies with the current administration during an interview with NPR, saying, “I think inequality can be a problem. And interestingly, seems to be getting a little bit worse under this administration. Income inequality is worse in towns run by Democrat mayors than it is in towns run by Republican mayors.”

Democratic Senator Charles Shumer urged Americans to focus on bolstering the middle class rather than on shaming the upper class, saying, “The focus had to be on how to get middle-class incomes up, rather than drive other people’s incomes down,” according to The Washington Post.

In a speech in October at Northwestern University, President Obama discussed education, a higher minimum wage, and changes to the tax rate of the richest Americans as a means of decreasing the growing financial divisions. "When nearly all the gains of the recovery have gone to the top one percent, when income inequality is at as high a rate as we’ve seen in decades, I find that a little hard to swallow that they really desperately need a tax cut right now," he said.

13) Are Taxes Really the Solution?

When it comes to closing the gap between the rich and the poor, more Americans seem to lean toward the idea of increasing taxes, particularly for the rich. In a 2014 poll by Pew Research Center, 49 percent of Americans said that high taxes could be a viable solution for reducing inequality, while less than 40 percent thought that lowering taxes would be helpful.

But it’s not immediately clear if simply increasing taxes on the richest Americans is the answer. While studies from some organizations, like the Economic Policy Institute, find that increasing taxes on high earners could help to reduce overall inequality, research from others, like the Tax Foundation, finds that a hefty increase in the tax rate for high earners might have other negative effects, like decreased wages and a lowered GDP.

There are other options too, like changing portions of the tax code that would decrease the ability to reduce taxable income. Research from the OECD found that an increase in the marginal tax rate on upper-income citizens may in fact fail to have the desired impact, thanks to these loopholes. In a 2014 op-ed for the Washington Post, former Treasury secretary Larry Summers advocated for closing such tax loopholes in an effort to extract more tax money from the richest individuals and companies, and redistribute it among the majority.

14) Stay in School

In the quest to bridge, or at least narrow, the gap of income inequality, education is one of the most frequently discussed solutions. Unsurprisingly, economists have found correlations between an increase in education and an increased level of earning. But some experts disagree on what type of education will best serve low-income families, and allow them to achieve higher earnings and more financial stability. This year, the Obama administration has pushed for higher education institutions to make a concerted effort to help students, and potential students, from low-income households enter college—arguing that a college degree is the best route to higher earnings.

But some believe that help should instead be targeted at K-12 education—giving children in lower-income families a solid educational foundation that will likely spur them to aspire to attend college or get a more-skilled job. And others think that increasing skills-based education is the answer to helping low-income households earn more, by allowing for more highly-skilled, technical work that will provide consistent, stable income.

15) Can Computers Save the Day?

Since the beginning of modern capitalist thought, theorists have pondered whether technological advances create more and better jobs than they destroy. Historically, it's common to perceive new technology as an enemy when the economy is slow. It's what John Maynard Keynes called "technological unemployment.”

But some economists—like George Mason University's Tyler Cowen—see the potential for technological advancements to create new jobs for middle-class workers. For example, as computers get easier to use and as education becomes cheaper and more widely available, Cowen thinks it’s possible that low-skilled workers could benefit from technological advances by using them to perform higher-function jobs. As technological advances hit developing economies (such as China's and India's), middle class Americans will benefit from better and safer products.

16) The Geography of Inequality

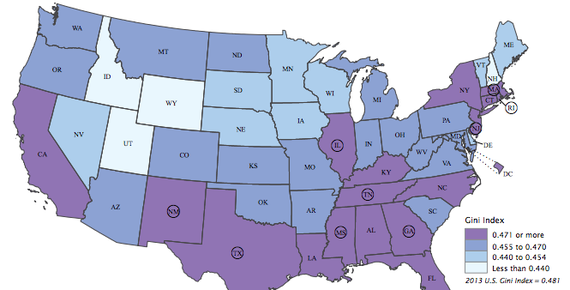

Income inequality is often measured by the Gini coefficient, a number between 0 (when everyone's equal) and 1 (total inequality)—though critics argue that this measure has its problems. In 2014, the Census Bureau reported that the Gini index for 2013 was 0.479, which was not statistically different than 2012. But it is up 4.9 percent from 1993.

At the state level, the Gini index is highest in America in states in the South, the Northeast, and California. 15 states saw their Gini index go up in 2013. For metropolitan areas in the U.S., Bridgeport-Stamford-Norwalk, Connecticut, tops the list for inequality, with the average income of the top 5 percent at $782,000 while the average income of the lowest 20 percent is $15,800. Ogden-Clearfield, Utah, ranked as the city with the lowest income inequality in 2013 with a Gini index of 0.394.

17) Inequality: It's Everywhere

Some say that global income inequality is falling. Some say maybe not. A report by Oxfam found that the gap between the rich and the poor is growing worldwide. The number of billionaires in the world has doubled since the financial crisis. The wealth of the world’s 1,646 billionaires combined is $5.4 trillion—a third of the U.S. yearly GDP—while there are 870 million people living in extreme poverty. Oxfam calculated that the revenues from a 1.5 percent tax on the wealth of the world’s billionaires could save 23 million lives if put into healthcare, or put every child in the world into school if used for education.

Income inequality in OECD countries is at its highest level in the past half century. Looking at the richest 10 percent of the population, the OECD reports that their average income is nine times that of the poorest 10 percent—up from only seven times 25 years ago.

Though the problem isn’t solely an American one, the U.S. ranks highest when it comes to inequality in developed nations, according to the OECD. The issue doesn’t seem like something that will be solved soon. In fact, challenges related to growing income inequality were listed as the number one global concern going into 2015 in a report from the World Economic Forum.